Maestro Auguin is currently in Australia rehearsing with the orchestra for Opera Australia’s production of The Ring Cycle. This is a cycle of 4 operas by the German composer Wagner, lasting a total of 15 hours!

We talk to him at length about Wagner’s music and this production, about the role of the conductor and his relationship with the composers and the musicians in the orchestra, which he says is like “playing a kind of invisible ping-pong with 30 people at the same time“.

In conversation with Maestro Auguin, we learn a lot about the philosophy and history of Wagner’s opera. Just as this opera has four parts, our interview has three, so we’re publishing the interview across three weeks.

Maestro Auguin, we find very little about you when we do our research. I don’t know if that’s intentional or not.

No. I think that in my profession it’s the result that counts, and that’s what keeps us going in life, in the profession. The rest are things that are peripheral and that are not really highly esteemed by musicians, and generally speaking, a conductor is not a pop star. That’s all there is to it.

Even so, I think it’s interesting to know where someone came from, how they decided to take this path and all that? How did you become a conductor? Did you play a musical instrument first? And what made you decide that you’d rather be in this job?

Well, the motivation that led me to start studying music was that I loved music. And as there was no one around me to tell me, watch out, this composer, this music is complicated and all that, I became acquainted with music written in the 18thᵉ century, music that was considered modern music for the 20th century. I had a devouring appetite, a passion in the first sense of the word. That is, I wanted to absorb all that all of that beauty, I wanted to understand it.

Conducting, in reality, is an extension of learning when you want to do it, learning to understand music from the inside. In other words, the musical instrument is one thing, of course, you have to play it, whether it’s the piano, the violin, the horn, the trumpet, the clarinet, whatever you like, or the organ, which is a world unto itself. But you learn to see how the composer arranged the notes. It was Mozart who said “I write together, I write notes that love each other.” I find that very beautiful. That was his way of describing it. And how did Mozart see that two notes loved each other? Why did he have to write this and that? I wanted to understand music from the inside, whether it was Johann Sebastian Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, Wagner, Schoenberg, Bergues or Webern.

For example, the composers of the Second Viennese School. In reality, even if we always bundle them together, Alban Berg, Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern are completely different people. Schoenberg was a kind of Beethoven of the 20thᵉ century. Berg was a romantic composer, and Webern was really a classical composer in his way of seeing things.

And so it’s seeing not just how it’s done, but why it was done the way it was. And the further along you get, the more you want to implement what you’ve learned.

So first of all, I like to share what makes me happy. That’s a constant in my life, and being with musicians, you communicate with them in the same way, accompanying them step by step. So, of course, very often they know the text very well, but from their point of view, I’m there to give them some light by saying to a musician who plays in a band that, yes, “you’ve got this to play, but there’s this as well. So look, these are the aspects that are there.”

It was something Carlo Maria Giulini said to the Orchestre de Paris when he conducted La mer there in the 70s and 80s. He said, “You know Debussy’s La mer better than I do… perhaps.” And so he had highlighted elements that perhaps, over time or just for entirely practical reasons, had not been sufficiently precisely and lovingly identified by the musicians.

So in reality, I want to build, I want to make real the material whose richness I’ve acquired by dint of learning it. And that’s it. And for me, that’s my main motivation.

So it’s really about sharing what you’ve learned.

Yes, it is. I’d say my teacher is always the composer. To always be in contact with because the composer talks to you. Why does he write such and such a note, such and such a thing? A composer spends his life creating difference. They want to make a difference.

And so, as a conductor, I’d come along and iron it out, and I’d say yes, it’s all the same, or no. And there are also private jokes made by someone like Richard Strauss, for example. He’s a specialist in that. He has musicians who are not at all accustomed to playing a solo, and he’ll put in something that the conductor will detect by saying ah yes, he wrote that just to get a certain sound with more timidity from the third oboe, who never plays a solo, compared to the first.

Whereas Wagner will give solos to absolutely everyone, the first, but also the second trumpet, the third trumpet, the third trombone, the fourth trombone, the third oboe. It’s the first time this has ever happened in the history of music. So you see the way the composer [does things and] you feel like you know them. These people talk to you about Schumann through the music.

Through all the time I’ve invested in trying to understand it as best I could, within my limited means. Well, I feel like I know Schumann. I have more in common, I share more with a composer who’s been dead for a long time or with a musician I wouldn’t see before or after rehearsal than I see you when I pass him in the corridor, I share more with musicians than with even people I rub shoulders with in a different way every day. We have more in common, and that’s the beauty of it.

Music is ephemeral, but the memory of music lasts forever. I saw a musician two years ago. I was back conducting in Germany. I hadn’t seen him for 25 years. The musician said to me, “Ah, do you remember back then, when you conducted such and such a symphony, such and such a passage?” I’d told the musicians that I’m always formal. He said it was February 1992, and do you remember?” So, all these things, there’s a kind of emergent quality – something that appears, that’s more than the sum of its parts. These things linger forever. There are many, many musicians. You ask them a question and they remember such and such a symphony on such and such a day with such and such a conductor. There’s something special about it. And it stays with you forever, forever.

It’s very touching.

It’s very human, very human. Why is it that in our childhood, we remember such and such a phrase, with all the millions of phrases, words we heard in our childhood, why is there such and such a passage, such and such a thing that sticks? And that’s why music is so closely linked to memory. When you stop at the last note, you don’t have the impression that something is finished. It’s an accomplishment, an enrichment. It’s something you take with you.

That’s beautiful. Perhaps you have a career as a philosopher too!

No, not at all. But I’m interested in a lot of things.

And you have a lot of experience in opera, but also in symphonic music.

Yes, of course I have. In other words, it’s all part and parcel, isn’t it? First of all, you have to know what conducting is. In reality, you’re the representative, the incarnation of the composer in front of the orchestra. Why is that? Because we’ve absorbed everything the composer has written in a work, and we’ve also gone beyond the notes.

So we’re there to coordinate the musicians’ efforts when they play. We’re also there to guide them aesthetically. We’re also a coach, quite simply to train them for a marathon, because even a very short symphony is something that needs to be organised mentally and physically, to measure out the effort, to distribute the difficulties, to build bridges musically.

So we have all these roles, and what’s more, the advantage we have over a stage director is that we’re also in the moment when we’re bringing the work to the audience, we’re part of it, we’re an actor as well as a stage director, a coach, a preparer.

And also, let’s say that [the conductor is] the person who has spent the most time understanding what the composer wanted, in the same way that we all use the same words, of course, we don’t all put the same meaning behind the same words, behind the same sensations. Something that’s blue to me may not be blue to someone else. Of course, the ancient Greeks didn’t have a word for blue, but they thought the sea was the colour of wine, which seems strange to us. And there are 16 ways of saying dawn in Provençal.

So, it’s philological work and research that really needs to be done. We have to make the link between the poetic vision, the composer’s idea, then the way he put it in black and white, and then it’s up to us to find and create what he wanted to do. It’s a bit like the curator at the Louvre having to repaint the Mona Lisa every morning for the 10 a.m. opening.

The musicians may get to rest during parts of the performance when other parts of the orchestra play but you have to be attentive during the whole performance.

There’s an interesting thing if it’s about tone that you have to have. Even if the movement is visually identical, if the conductor – I’m talking about myself – if internally you try to rest, to disconnect for four bars instantly, the sound of the orchestra disappears. It’s like a breath taken away all at once. There’s nothing left. The musicians sense that we’re always in positive tension, that we’re always in anticipation, that we’re always in what we’re doing now and what we’re going to do next.

I’m always, even for an instrument, I’m entirely 100% what the Anglo-Americans sports people call “to be in the zone”. You’re always, all the time in the action, in the concentration, in the thing. At the moment when we create this thing because we’ve created it – of course, we have the notes, but behind each note, there’s a human being playing it. All you hear is there’s someone playing all the time, all the time, all the time, all the time. Well, it’s up to me to always be with that person, whether it’s one or whether it’s 120 musicians and 80 backing singers, well, I’m always with them.

The musician is constantly connected to me and to the text. It’s a kind of silent dialogue between the musician and I. (S)He gives me something, I do something with it. He gives me something, I do something with it, I send it back to him’her, (s)he sends it back to me. As far as cohesion is concerned, that’s the most basic thing. It’s like a GPS: you go left twice, right once, for example.

Then, it’s really like playing a kind of invisible ping-pong with 30 people at the same time, or in other words, I give information but it’s not a kind of package deal. It’s always information for everyone. Everyone, the first horn, the first trumpet, the violins. It’s always for everyone at the same time.

I listen to the orchestra. Listening to the orchestra is my way of absorbing the information they send me. I send visual information, they send me auditory information and depending on how this auditory information arrives, it’s a reflection of the information I’ve given. So I can see how the information has been understood by the musician, how (s)he’s worked on it, how (s)he’s digested it, how (s)he’s transmitted it in the text, in his way of writing and playing. So I send them visual information. They send me auditory information, and depending on how I see (s)he’s understood it, I either let it go or adjust it. I do a little faster, a little slower, a little earlier, a little later, a little louder, a little softer, expressive or rather softer, or rather longer, or shorter. So it’s a sort of ping-pong game every time, a game of ping-pong with 30 or 50 people.

And at the same time, once you’re past that stage, you’re in the work. In other words, we’re at the point where we’re creating the work for the musicians, as well as for the audience. In reality, it’s something that’s self-created as we create it. Yes, we create the work, the musician creates the work as we play it.

—

We’ll continue our interview with Maestro Auguin next Friday, when he talks about Wagner’s music and Opera Australia’s production of The Ring Cycle that Maestro Auguin is conducting, more specifically.

KEY INFO FOR THE RING CYCLE WITH MAESTRO AUGUIN

WHAT: The Ring Cycle with Maestro Auguin as conductor

WHERE: The Lyric Theatre, QPAC, BRISBANE

WHEN: You can choose from three different cycles for this series of four operas.

Cycle 1; Dec. 1, 2023 7pm, Dec. 3, 2023 1pm, Dec. 5, 2023 5pm, Dec. 7, 2023 4pm

Cycle 2: Dec. 8, 2023 7pm, Dec. 10, 2023 5pm, Dec. 12, 2023 5pm, Dec. 14, 2023 4pm

Cycle 3: Dec. 15, 2023 7pm, Dec. 17, 2023 5pm, Dec. 19, 2023 5pm, Dec. 21, 2023 1pm

HOW: The Ring Cycle is a special event, sold either as a series of four operas, or as individual operas.

You can buy tickets for all four operas as a complete cycle, with the same seat for each opera. These performances have been rescheduled from last year, so many seats have already been purchased. The best availability is in cycle 3.

Ticket buyers will now have the option to build their own variable package, for those wanting to view more than one production, and to mix and match dates across the three-week season.

You can purchase tickets via this link

HOW MUCH: Tickets are available for complete cycles of four operas (or for individual operas). There are no concessions. Ticket prices for the full cycle are as follows:

- Premium $2360

- Reserve A $1960

- Reserve B $1200

- Reserve C $520

Tickets to the individual Ring operas (single tickets) start at $165 and bookings of two or more performances qualify buyers for a discounted rate. Reserve Single tickets pricing are as follows (before any discounts for purchasing tickets to several productions):

- Premium $625

- A Reserve $525

- B Reserve $335

- C Reserve $165

—

We’ll continue our interview with Maestro Auguin next Friday, when he talks about Wagner’s music and Opera Australia’s production more specifically.

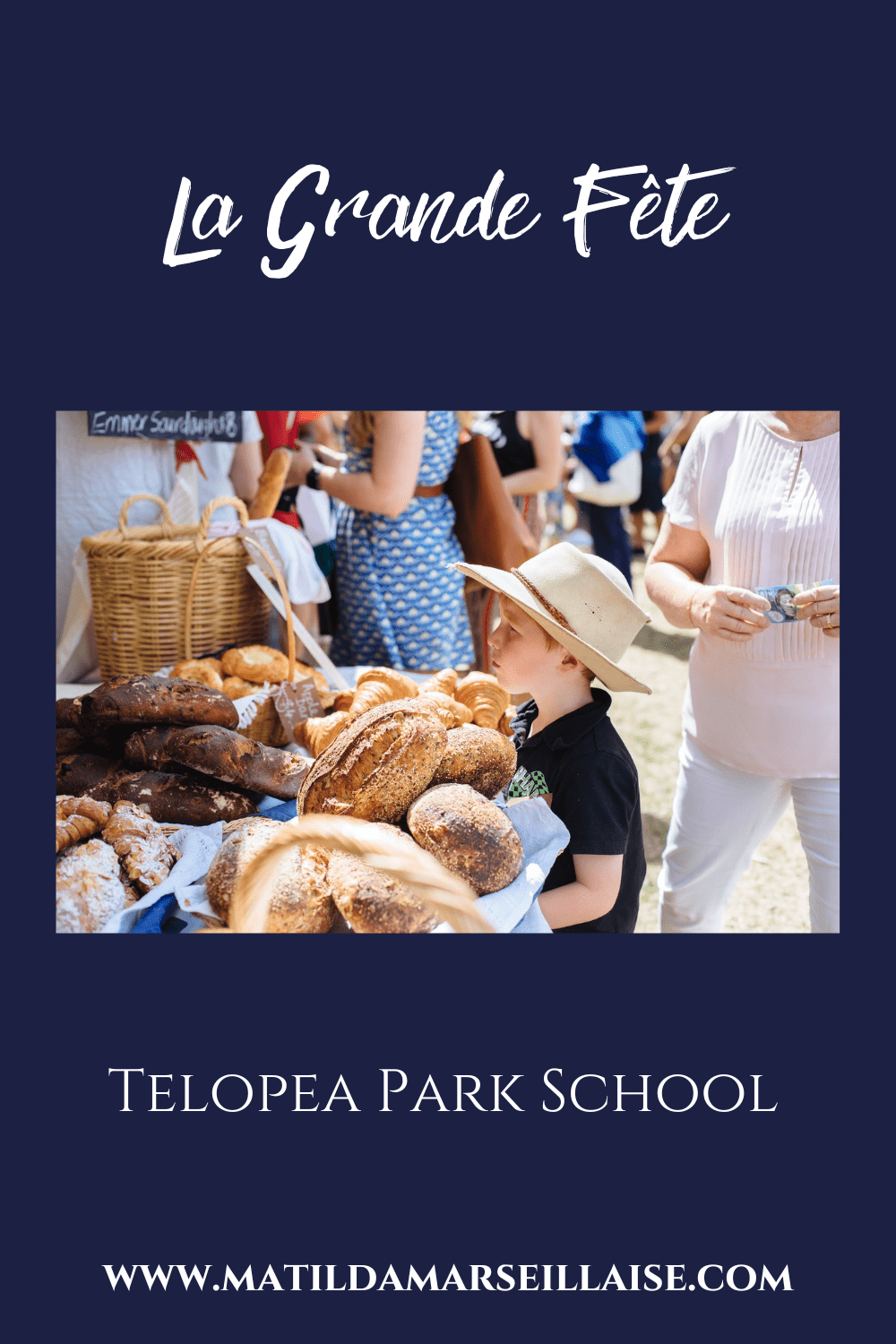

For events with links to France and the Francophonie, check out our What’s on in November.